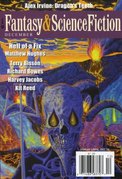

| Editor: | Gordon van Gelder |

| Issue: | Volume 117, No. 5 |

| ISSN: | 1095-8258 |

| Pages: | 258 |

The editorial in this issue is the result of the F&SF 30th anniversary competition in 1980, which asked readers to make a prediction about the future of 2010 for a cash prize in 2010. This is a great idea and made for interesting reading (a letter from the winner, who predicted hand-held computers, is reprinted). Impressive for a magazine to last long enough to complete such a contest.

The other non-fiction highlight of this issue was, for a change, Charles de Lint's review column, in which he surveys non-fiction. As an avid reader of non-fiction (particularly SF-related non-fiction) as well as fiction, more of this please.

"Dragon's Teeth" by Alex Irvine: This is a sort-of-sequel to "Wizard's Six," which I see I mildly enjoyed but didn't remember. That story went into more depth concerning the magic system; this story is about an adventure to kill a dragon, undertaken by a man who had previously raided a tomb and carried away a strange treasure. The killing of the dragon is equally strange, and then shifts to a recovery whose point I didn't entirely follow. This is more original by far than "Wizard's Six," but also quite a bit more confusing. I think I would have liked it better if I'd understood it more. (6)

"Bad Matter" by Alexandra Duncan: Usually in stories about cultural difference between star-travelers and a planetary population, the reader seems meant to identify with the star-travelers and see the planet as other. This story inverts that, showing a star-traveling people with a pattern of life that felt to me like a throwback, a sort of communal Amish-inspired feel (but with some extra sexism). The story is overtly anthropological, with a protagonist who is the daughter of an anthropologist. It starts as a cultural picture (enlivened with footnotes) and turns on a point of ritual and connection. It started out intellectually appealing and became emotionally touching in a way that surprised me. One of the better stories in this issue. (7)

"Farewell Atlantis" by Terry Bisson: I liked the hook of this story: two people in a theater who slowly realize that the theater isn't what they thought and that they were just waking up there from a sort of dream. They find themselves on a spaceship, having been brought out of suspended animation through exposure to culture from movies. The story is about discovering who they are, where they came from, why they were woken, and what the point of it all was. That was looking quite promising, but the revelation, when it comes, was unworthy of the setup and left the story flat. (6)

"Hell of a Fix" by Matthew Hughes: Hughes is best known for his Vancian far-future fin de siècle stories, but his writing is strong even outside of that mode. This is one of his rare present-day stories, and I think it may be the best of his I've ever read.

Chesney is an actuary who, at the beginning of the story, accidentally summons a demon (in a way that's funny enough to be worth the price of admission by itself). He's then offered the standard contract: his soul for pretty much whatever he wants. Which he turns down. Repeatedly, with actuarial persistance. And that sets off all sorts of unforseen consequences that turn into a very entertaining and creative story. Worth seeking out, and the best story of the issue. (8)

"Illusions of Tranquility" by Brendan DuBois: Most SF about the space program is either optimistic boosterism or excited adventure, so it's worth noting when a story comes along that looks at how similar human problems are likely to be even when set on the moon. This one looks at an economically impoverished moon base, existing primarily on its illusions and the money of VIPs, and what it does to stay alive. It's essentially a take on the old small-town escape story, but with a setting that turns it into a deeper commentary on how humans bring their social structure problems with them and cling to their desire for illusions. A bit depressing, but the likeable protagonist makes up for it. (7)

"The Blight Family Singers" by Kit Reed: A slight humor story about a traveling singing family, a town who wants their money but isn't too interested in their music, and a creepy family patriarch. It has an ending twist that was mildly surprising, but the foundation of the story is a repetitive pattern of showing disgusted reactions to one character and then shifting to the viewpoint of that character to see why they act the way they do. Like a lot of humor, it's hit or miss; for me, it was mostly miss. (4)

"The Economy of Vacuum" by Sarah Thomas: This is apparently the issue for desperate and depressing space program stories. Virginia is a lone astronaut sent to a moon base for extended human habitation, sent supplies regularly from Earth. She's still there when things go horribly wrong on Earth, and the story follows a descent into madness that's more effective for not trying to be stream of consciousness or excessively overwrought. This one is depressing straight to the end, but it's still oddly compelling for reasons that I can't quite identify. Maybe it's the elfin nature of Virginia's madness, and the sense that she's reached some sort of untouchable peace. (6)

"Iris" by Nancy Springer: A short look at an elderly woman, a Christmas ritual, and grief. It stays this side of maudlin, but only barely, and the SFnal element is one of those heart-warming bits of emotional resonance that I have a hard time truly believing in. I think one's reaction to this story will vary depending on whether it connects with emotions already present inside, and for me there was nothing for it to click with. (5)

"Inside Time" by Tim Sullivan: "Inside Time" opens with the protagonist being rescued by an automated station with only one inhabitant. He's somewhere outside of normal spacetime in a time station, one where rescued people from weird time loops end up. The story starts as if it's going to be a type of Big Dumb Object story, explaining what's going on, but it takes a more pscyhological twist and puts the protagonist's relationship with the lone woman who was already in the station at the center of the story. The climax comes when another person is rescued, and their companionship is strained by competition. I'm not sure I bought the ending, which seemed too simple and moralistic, but the story background and construction kept me entertained. (6)

"The Man Who Did Something about It" by Harvey Jacobs: Colin Kabe is an automobile mechanic, one of those wizards with machinery who can repair almost anything. But he starts the story with another desire: to finally do something about the it that everyone wants to do something about and doesn't. Then he gets asked to fix someone's spaceship in circumstances with a strong Douglas Adams resonance. This is a story about fixing things, one that sidles up to an elusive feeling without talking about it directly and then hints at it in the end of the story in a way that I found startlingly effective. I'm not sure everyone will get the same thing out of it that I did, but I liked it a lot. (7)

"I Needs Must Part, the Policeman Said" by Richard Bowes: I suspect I'd get a lot more out of this story if I'd read the Dick novel with the similar title, since this is clearly a reference. As is, I found it a bit confusing, and it didn't stick well in my head. I'm also not a huge fan of reading a book about someone sick with a bowel obstruction, particularly one that goes into occasional medical detail. But, that said, the way in which its metaphysical component unfolds is quietly effective, and I bought the emotional tone at the end. I like looks at life and death that aren't either as fraught or as absolute as the normal presentations. (6)

Reviewed: 2011-05-28