| Editor: | Sheila Williams |

| Issue: | Volume 34, No. 2 |

| ISSN: | 1065-2698 |

| Pages: | 112 |

Silverberg's column continues to be reliably entertaining and the best regular non-fiction column in either Asimov's or F&SF. This issue, he looks back on some of Clarke's early work, discussing both their features in his memory and some of their shortcomings when read with a more skeptical eye. This is interesting stuff, better than nearly all book review columns. Heck's column in the same issue is somewhat overshadowed, but does describe an interesting selection of new books.

"Stone Wall Truth" by Caroline M. Yoachim: I'm not sure what to make of this story. It's about a woman whose job it is to flay and essentially disassemble people against a giant wall as a form of punishment, putting a stone in their mouth that holds their spirit while they're on the wall. Then, when they're taken down again, she sews them back together, allowing them to return to life. That's the setting; the story explores what the wall is, how it's used politically, and what to make of the experience of it. It's one of those stories that mixes hinted philosophical exploration with the puzzle of what the heck is going on. I'm not sure if I missed some of it, or if the emotional undercurrent just didn't resonate with me. There's something skillful here that didn't quite click, and it might just be me. (6)

"Dead Air" by Damien Broderick: People have tried one of the desperate schemes to fight global warming: a space installation at Earth-Sun L1 to shield some of the sun's radiation from earth. Shortly thereafter, parades of people without sound, people who seem to be dead, started taking over more and more channels of the television. This short story is sort of about who those people are and what's going on, but it's more about the conspiracy theories that people come up with and the psychological reactions to something so strange happening. It's written as an homage to Philip Dick, and it has that sense of slipping, twisting reality that Dick has. Not really my thing, but if it's yours, it seems like a good example of the type. (5)

"The Woman Who Waited Forever" by Bruce McAllister: This story starts out as a portrait of social class dynamics around a military base in Italy during the Cold War, shifts into childhood group dynamics, and then turns towards the supernatural. I'd be spoiling it somewhat to say what type of story it is in the end, but it does a fairly good job at atmosphere. My main complaint is that I really disliked most of the characters, and the story setup relied on kids doing some stupid and destructive things that are realistic but lead me to dislike kids. I also don't get the emotional tone of the ending or the narrator's conclusion at all, which left a decidedly sour note. (6)

"The Bold Explorer in the Place Beyond" by David Erik Nelson: It's hard to really dislike a story about a squid who invents a mechanical exploration vessel to venture into the Place Beyond, namely our world (even if Karen Traviss had done the idea better in the Wess'Har series). The understated background of a possibly steampunk world with clockwork soldiers was also mildly appealing. Unfortunately, Nelson set both in one of the more annoying frames that I can think of. The story is told in heavy dialect by a somewhat disgusting drunk, and is heard by a boy with embarassingly stupid (and conventionally sexist) ideas about peeking at girls. I think I would have enjoyed the story in a different frame, but that ruined it for me. (4)

"The Wind-Blown Man" by Aliette de Bodard: This is the first story of this issue that I really liked. I will warn up-front that there may be some orientalism in its portrayal of an Imperial Court with Chinese-sounding names and a monestary high in the mountains; I'm not the best reviewer to judge and tend to be under-sensitive to that. But the underlying story feels like it's own mix of culture: a form of transcendence that involves self-denial and withdrawal, but that slowly develops a surprising twist over the course of the story, and which is far from clearly a good thing. It plays with both auras and elemental (or humour) balance in people, and with training others for something one cannot do oneself. I'm not sure I bought the ending, but I loved the atmospheric feel de Bodard creates. (8)

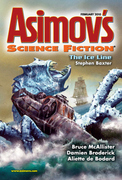

"The Ice Line" by Stephen Baxter: This is a sequel to "The Ice War" and is somewhat related to Baxter's novel Anti-Ice. It's an alternative history in the Napoleonic era (85 years later than "The Ice War") that adds to the European conflict the lingering threat from aliens who have thrived in the frozen north of the world. It's also a rather rare find: a Baxter story that I actually enjoyed reading.

The story purports to be the diary of Ben Hobbes, supposed assistant to Robert Fulton in building naval submarines. It starts in the middle of a sea battle against Napoleon, but shifts quickly to a secret British mission concerned with the aliens set against the backdrop of a Napoleonic invasion of Britain. But one of the best parts is that this diary was supposedly discovered by Anne Collingwood, another character in this story, and she adds footnotes and "corrections" to it at various points. That interplay is more fun that the interplay between her and Ben in the main story, and while the plot is still a bit too pulp for my taste, it's quite a bit more interesting than typical Baxter fare. I wouldn't actively seek this one out, but it was quite a bit better than I expected. (7)

Reviewed: 2011-06-06