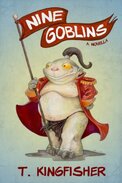

The goblins are at war, a messy multi-sided war also involving humans, elves, and orcs. The war was not exactly their idea, although the humans would claim otherwise. Goblins kept moving farther and farther into the wilderness to avoid human settlements, and then they ran out of wilderness, and it wasn't clear what else to do. For the Nineteenth Infantry, the war is a confusing business, full of boredom and screaming and being miserable and following inexplicable orders. And then they run into a wizard.

Wizards in this world are not right in the head, and by not right I mean completely psychotic. That's the only way that you get magical powers. Wizards are therefore incredibly dangerous and scarily unpredictable, so when the Whinin' Nineteenth run into a human wizard who shoots blue out of his mouth, making him stop shooting blue out of his mouth becomes a high priority. Goblins have only one effective way of stopping things: charge at them and hit them with something until they stop. Wizards have things like emergency escape portals. And that's how the entire troop of nine goblins ended up far, far behind enemy lines.

Sings-to-Trees's problems, in contrast, are rather more domestic. At the start of the book, they involve, well:

Sings-to-Trees had hair the color of sunlight and ashes, delicately pointed ears, and eyes the translucent green of new leaves. His shirt was off, he had the sort of tanned muscle acquired from years of healthy outdoor living, and you could have sharpened a sword on his cheekbones.

He was saved from being a young maiden's fantasy — unless she was a very peculiar young maiden — by the fact that he was buried up to the shoulder in the unpleasant end of a heavily pregnant unicorn.

Sings-to-Trees is the sort of elf who lives by himself, has a healthy appreciation for what nursing wild animals involves, and does it anyway because he truly loves animals. Despite that, he was not entirely prepared to deal with a skeleton deer with a broken limb, or at least with the implications of injured skeleton deer who are attracted by magical disturbances showing up in his yard.

As one might expect, Sings-to-Trees and the goblins run into each other while having to sort out some problems that are even more dangerous than the war the goblins were unexpectedly removed from. But the point of this novella is not a deep or complex plot. It pushes together a bunch of delightfully weird and occasionally grumpy characters, throws a challenge at them, and gives them space to act like fundamentally decent people working within their constraints and preconceptions. It is, in other words, an excellent vehicle for Ursula Vernon (writing as T. Kingfisher) to describe exasperated good-heartedness and stubbornly determined decency.

Sings-to-Trees gazed off in the middle distance with a vague, pleasant expression, the way that most people do when present at other people's minor domestic disputes, and after a moment, the stag had stopped rattling, and the doe had turned back and rested her chin trustingly on Sings-to-Trees' shoulder.

This would have been a touching gesture, if her chin hadn't been made of painfully pointy blades of bone. It was like being snuggled by an affectionate plow.

It's not a book you read for the twists and revelations (the resolution is a bit of an anti-climax). It's strength is in the side moments of characterization, in the author's light-hearted style, and in descriptions like the above. Sings-to-Trees is among my favorite characters in all of Vernon's books, surpassed only by gnoles and a few characters in Digger.

The Kingfisher books I've read recently have involved humans and magic and romance and more standard fantasy plots. This book is from seven years ago and reminds me more of Digger. There is less expected plot machinery, more random asides, more narrator presence, inhuman characters, no romance, and a lot more focus on characters deciding moment to moment how to tackle the problem directly in front of them. I wouldn't call it a children's book (all of the characters are adults), but it has a bit of that simplicity and descriptive focus.

If you like Kingfisher in descriptive mode, or enjoy Vernon's descriptions of D&D campaigns on Twitter, you are probably going to like this. If you don't, you may not. I thought it was slight but perfect for my mood at the time.

Reviewed: 2020-11-27