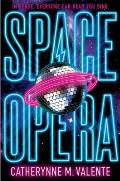

| Publisher: | Saga |

| Copyright: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 1-4814-9751-0 |

| Format: | Kindle |

| Pages: | 304 |

This is an ebook, so metadata may be inaccurate or missing. See notes on ebooks for more information.

Life is not, as humans had come to think, rare. The universe is packed with it, bursting at the seams. The answer to the Fermi paradox is not that life on Earth is a flukish chance. It's that, until recently, everyone else was distracted by total galactic war.

Thankfully by the time the other intelligent inhabitants of the galaxy stumble across Earth the Sentience Wars are over. They have found a workable solution to the everlasting problem of who counts as people and who counts as meat, who is sufficiently sentient and self-aware to be allowed to join the galactic community and who needs to be quietly annihilated and never spoken of again. That solution is the Metagalactic Grand Prix, a musical extravaganza that is also the highest-rated entertainment in the galaxy. All the newly-discovered species has to do is not finish dead last.

An overwhelmingly adorable giant space flamingo appears simultaneously to every person on Earth to explain this, and also to reassure everyone that they don't need to agonize over which musical act to send to save their species. As their sponsors and the last new species to survive the Grand Prix, the Esca have made a list of Earth bands they think would be suitable. Sadly though, due to some misunderstandings about the tragically short lifespans of humans, every entry on the list is dead but one: Decibel Jones and the Absolute Zeroes. Or their surviving two members, at least.

Space Opera is unapologetically and explicitly The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy meets Eurovision. Decibel Jones and his bandmate Oort are the Arthur Dent of this story, whisked away in an impossible spaceship to an alien music festival where they're expected to sing for the survival of their planet, minus one band member and well past their prime. When they were at the height of their career, they were the sort of sequin-covered glam rock act that would fit right in to a Eurovision contest. Decibel Jones still wants to be that person; Oort, on the other hand, has a wife and kids and has cashed in the glitterpunk life for stability. Neither of them have any idea what to sing, assuming they even survive to the final round; sabotage is allowed in the rules (it's great for ratings).

I love the idea of Eurovision, one that it shares with the Olympics but delivers with less seriousness and therefore possibly more effectiveness. One way to avoid war is to build shared cultural ties through friendly competition, to laugh with each other and applaud each other, and to make a glorious show out of it. It's a great hook for a book. But this book has serious problems.

The first is that emulating The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy rarely ends well. Many people have tried, and I don't know of anyone who has succeeded. It sits near the top of many people's lists of the best humorous SF not because it's a foundational model for other people's work, but because Douglas Adams had a singular voice that is almost impossible to reproduce.

To be fair, Valente doesn't try that hard. She goes a different direction: she tries to stuff into the text of the book the written equivalent of the over-the-top, glitter-covered, hilariously excessive stage shows of unapologetic pop rock spectacle. The result... well, it's like an overstuffed couch upholstered in fuchsia and spangles, onto which have plopped the four members of a vaguely-remembered boy band attired in the most eye-wrenching shade of violet satin and sulking petulantly because you have failed to provide usable cans of silly string due to the unfortunate antics of your pet cat, Eunice (it's a long story involving an ex and a book collection), in an ocean-reef aquarium that was a birthday gift from your sister, thus provoking a frustrated glare across an Escher knot of brilliant yellow and now-empty hollow-sounding cans of propellant, when Joe, the cute blonde one who was always your favorite, asks you why your couch and its impossibly green rug is sitting in the middle of Grand Central Station, and you have to admit that you do not remember because the beginning of the sentence slipped into a simile singularity so long ago.

Valente always loves her descriptions and metaphors, but in Space Opera she takes this to a new level, one covered in garish, cheap plastic. Also, if you can get through the Esca's explanation of what's going on without wanting to strangle their entire civilization, you have a higher tolerance for weaponized cutesy condescension than I do.

That leads me back to Hitchhiker's Guide and the difficulties of humor based on bizarre aliens and ludicrous technology: it's not funny or effective unless someone is taking it seriously.

Valente includes, in an early chapter, the rules of the Metagalactic Grand Prix. Here's the first one:

The Grand Prix shall occur once per Standard Alumizar Year, which is hereby defined by how long it takes Aluno Secundus to drag its business around its morbidly obese star, get tired, have a nap, wake up cranky, yell at everyone for existing, turn around, go back around the other way, get lost, start crying, feel sorry for itself and give up on the whole business, and finally try to finish the rest of its orbit all in one go the night before it's due, which is to say, far longer than a year by almost anyone else's annoyed wristwatch.

This is, in isolation, perhaps moderately amusing, but it's the formal text of the rules of the foundational event of galactic politics. Eurovision does not take itself that seriously, but it does have rules, which you can read, and they don't sound like that, because this isn't how bureaucracies work. Even bureaucracies that put on ridiculous stage shows. This shouldn't have been the actual rules. It should have been the Hitchhiker's Guide entry for the rules, but this book doesn't seem to know the difference.

One of the things that makes Hitchhiker's Guide work is that much of what happens is impossible for Arthur Dent or the reader to take seriously, but to everyone else in the book it's just normal. The humor lies in the contrast.

In Space Opera, no one takes anything seriously, even when they should. The rules are a joke, the Esca think the whole thing is a lark, the representatives of galactic powers are annoying contestants on a cut-rate reality show, and the relentless drumbeat of more outrageous descriptions never stops. Even the angst is covered in glitter. Without that contrast, without the pause for Arthur to suddenly realize what it means for the planet to be destroyed, without Ford Prefect dryly explaining things in a way that almost makes sense, the attempted humor just piles on itself until it collapses under its own confusing weight. Valente has no characters capable of creating enough emotional space to breathe. Decibel Jones only does introspection by moping, Oort is single-note grumbling, and each alien species is more wildly fantastic than the last.

This book works best when Valente puts the plot aside and tells the stories of the previous Grands Prix. By that point in the book, I was somewhat acclimated to the over-enthusiastic descriptions and was able to read past them to appreciate some entertainingly creative alien designs. Those sections of the book felt like a group of friends read a dozen books on designing alien species, dropped acid, and then tried to write a Traveler supplement. A book with those sections and some better characters and less strained writing could have been a lot of fun.

Unfortunately, there is a plot, if a paper-thin one, and it involves tedious and unlikable characters. There were three people I truly liked in this book: Decibel's Nani (I'm going to remember Mr. Elmer of the Fudd) who appears only in quotes, Oort's cat, and Mira. Valente, beneath the overblown writing, does some lovely characterization of the band as a trio, but Mira is the anchor and the only character of the three who is interesting in her own right. If this book had been about her... well, there are still a lot of problems, but I would have enjoyed it more. Sadly, she appears mostly around the edges of other people's manic despair.

That brings me to a final complaint. The core of this book is musical performance, which means that Valente has set herself the challenging task of describing music and performance sufficiently well to give the reader some vague hint of what's good, what isn't, and why. This does not work even a little bit. Most of the alien music is described in terms of hyperspecific genres that the characters are assumed to have heard of and haven't, which was a nice bit of parody of musical writing but which doesn't do much to create a mental soundtrack. The rest is nonspecific superlatives. Even when a performance is successful, I had no idea why, or what would make the audience like one performance and not another. This would have been the one useful purpose of all that overwrought description.

Clearly some people liked this book well enough to nominate it for awards. Humor is unpredictable; I'm sure there are readers who thought Space Opera was hilarious. But I wanted to salvage about 10% of this book, three of the supporting characters, and a couple of the alien ideas, and transport them into a better book far away from the tedious deluge of words.

I am now inspired to re-read The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, though, so there is that.

Reviewed: 2019-08-26