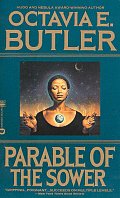

| Publisher: | Warner Aspect |

| Copyright: | 1993 |

| Printing: | February 1995 |

| ISBN: | 0-446-60197-7 |

| Format: | Mass market |

| Pages: | 295 |

The fall of civilization is one of science fiction's favorite themes. And yet, with all those books full of blockbuster alien wars, grand plagues, nuclear holocaust, and forgotten pasts, there are surprisingly few books that take a realistic look at what it would be like to live through one.

Most stories about the downfall of everything we know and love are the novel equivalent of blockbuster special effects movies (and often inspire the same). From Fritz Leiber's The Wanderer to more recent examples like Niven and Pournelle's Footfall, there are plenty of dramatic stories about the arrival of aliens (or disaster or war), told with a huge cast, many camera angles, and still shots to capture the drama of it all. It makes for a good movie with some lasting images, but the story tends to be about defeating the big bad, the triumph of our heroes, and a few exciting and photogenic deaths. Long-term coping isn't exactly the point.

Similarly, there are tons of post-holocaust survival stories. My personal favorite is David R. Palmer's Emergence, but there are numerous others. Sometimes our heroes are essentially alone. Sometimes there are a few other survivors (often bad guys, in some fashion or another). But often, while much is made of foraging and survival techniques and the like, the point of the novel borders on the utopian. The collapse and mass death of humanity isn't really the point. That's just the reset button the author uses to clear out the world so that we can focus on the interesting bits, whether that be isolation (Emergence), the cyclic nature of history (A Canticle for Leibowitz), or just a close-up view of a different type of life without the distractions of all those people (Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang). Some of these books are quite good, but the collapse of civilization feels like a plot device.

This extended introduction is an effort to explain why Parable of the Sower is so notable. From the back cover or a plot synopsis, you might not notice. It sounds like another post-holocaust story, mixed in with some weird spiritual stuff. Probably another reset button for utopia sort of story. And yet, it isn't at all.

The differences are illuminating, and the largest of them is that Butler's world is populated. In most of these stories, one gets two choices in inhabitants other than the primary cast: large sprawls of movie extras with occasionally close-ups on momentary stars (who then die horribly), or faceless exemplars of a particular group that the heroes are going to fight, avoid, or ally with. The cast is generally set within the first fifty pages and outside of that, the people aren't real, unless there are so few people left in the world that the cast is all that's left.

Butler's world couldn't be more different. Lauren starts out in a walled neighborhood and we get a detailed introduction to her family and neighbors. By the time bad things become a reality rather than a worry, we know enough about these people to care about them when they don't survive. And even afterwards, the cast is fluid, picking up and losing people, showing others on camera, and leaving the reader uncertain whether a character is only passing through or will stick around. It's subtle, but it lets the reader share some uncertainty and identify with the first-person viewpoint. There is no mass elimination of people for simplicity and authorial convenience; the world starts messy and stays messy.

Similarly, Butler talks about problems that normally get swept under the rug as all the good guys hunker down and do the right thing. Butler's world is dangerous. Helping someone isn't necessarily a good idea, but sometimes you do it anyway — and sometimes when you do it anyway, it backfires. Racism isn't something that only happens in obvious ways. Gender is an issue but doesn't completely control life. Simple political solutions fail messily when confronted with reality. Parable of the Sower contains a world that feels lived in, realistic, complex, and living. I didn't realize what I was missing in disaster fiction until I saw how much richer the world could be.

Notably, too, there is no plague, no invasion, no war. Civilization collapses because it's rotten. Things get a little bit worse each day, people get a little more desperate, the first few breakdowns are fixed, and then it becomes harder and harder to fix everything. History is full of such stories, but SF treatment of the theme tends towards explosions. The assumption of a grand triggering event is a form of hubris: the belief that no matter how bad things feel, it would still take a massive right hook to knock us out. In reality, collapses can be staggered, local, and largely ignored by those not directly affected until so widespread that it's too late to do much.

This is not a typical disaster novel, nor is it a cynical dystopia. It's the first-person journals of a teenager and then a woman who saw that things were getting worse, prepared herself as best she could, and then survived. There are few big explosions and few grand SF ideas; there are a lot of sharp political observations, an intriguing twist on religion, some excellent characters, and a distinct lack of black-and-white portrayals. If this sounds boring, don't worry, it's not. It probably would be in the hands of a lesser author who needs shiny special effects to paper over the places where the characters wear thin. Butler is not a lesser author, however, and she can keep you on the edge of your seat with character alone.

Highly recommended. This is the picture of future collapse that will stick with me and a narrator I want to read through it with.

Followed by Parable of the Talents.

Reviewed: 2006-03-12